I had never ridden an underground train before my first visit to London. My years in the Los Angeles area were happily behind me long before they built theirs, and my one short visit to New York was accomplished without the subway experience. I admit to having been somewhat intimidated by the idea of the Underground, but one visit convinced me there couldn’t be a simpler or faster way of getting around a big city. If you know which station you’re in and which one you’re going to, and if you can read, you can get there with little or no hassle for a little more than the price of a bus fare, and a lot less than a taxi.

While waiting to pick up a Britrail pass before a long-ago visit here, I overheard a travel agent telling a couple of clients that they might find the tube too intimidating, and perhaps they’d be better off learning the bus system to get around town. It was all I could do not to rush into her office and set them all straight (and you know I could, too…). I’ll grant you that aboveground travel has its advantages, especially for tourists, but even the most casual tourist owes it to her experience of London to check out tube travel, and anyone interested in getting from one place to another quickly and easily had better either pony up for cab fare or head underground.

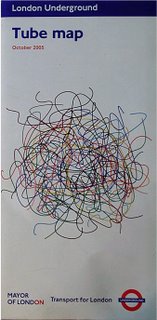

One of the things that makes tube travel simple is the universe-famous Tube Map, developed by an electrical draughtsman who did for the Metropolitan Railway what he did for electrical circuits: made it simple and easy to follow. By assigning a different color to each railway “wire,” and simplifying the geography considerably, Harry Beck created, 73 years ago, a travel diagram that’s been the inspiration for any transport map you’ve ever seen. Inside every train carriage is an even more simplified diagram of the line you’re riding, with the wire stretched out into a straight line. From any seat you can glance up and see where you are along your journey.

Everyone understands, of course, that the map is not the territory, and the Tube Map doesn’t represent the Underground exactly. But it wasn’t until last year, when Transport for London unveiled the actual map (see photo) that Londoners understood what a simplification it truly was. You can be sure they forgot again as soon as they possibly could.

Riding during rush hours can be a real sardine-tin experience, and during heat waves like the one we’ve been having here the last few weeks, you’ll hear recordings warning you to carry water. Last week a man was mugged for a 40p bottle of water by a well-dressed fellow-passenger whose thirst overcame him on a day when the recorded temperature underground was 47C (117F). When he wouldn’t surrender the water voluntarily, the aggressor snatched the bottle and drank from it until the train stopped at Bank, then he got off with it and walked away. I’d say carry some for yourself and some for your mugger.